The term "will-o'-the-wisp" comes from "wisp," a bundle of sticks or paper sometimes used as a torch, and the name "Will," thus meaning "Will of the torch." The term jack-o'-lantern (Jack of the lantern) has a similar meaning. In the United States, they are often called "spook-lights," "ghost-lights," or "orbs" by folklorists and paranormal enthusiasts.[2][3][4]

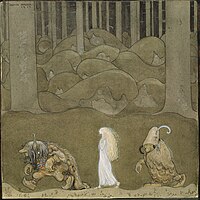

Folk belief attributes the phenomenon to fairies or elemental spirits, explicitly in the term "hobby lanterns" found in the 19th century Denham Tracts. Briggs' A Dictionary of Fairies provides an extensive list of other names for the same phenomenon, though the place where they are observed (graveyard, bogs, etc.) influences the naming considerably. When observed in graveyards, they are known as "ghost candles," also a term from the Denham Tracts.

The names will-o'-the-wisp and jack-o'-lantern are explained in etiological folk-tales, recorded in many variant forms in Ireland, Scotland, England, Wales, Appalachia, and Newfoundland.[citation needed] In these tales, protagonists named either Will or Jack are doomed to haunt the marshes with a light for some misdeed. One version from Shropshire is recounted by K. M. Briggs in her book A Dictionary of Fairies and refers to Will the Smith. Will is a wicked blacksmith who is given a second chance by Saint Peter at the gates of heaven, but leads such a bad life that he ends up being doomed to wander the earth. The Devil provides him with a single burning coal with which to warm himself, which he then uses to lure foolish travellers into the marshes.

An Irish version of the tale has a ne'er-do-well named Drunk Jack or Stingy Jack who makes a deal with the Devil, offering up his soul in exchange for payment of his pub tab. When the Devil comes to collect his due, Jack tricks him by making him climb a tree and then carving a cross underneath, preventing him from climbing down. In exchange for removing the cross, the Devil forgives Jack's debt. However, no one as bad as Jack would ever be allowed into heaven, so Jack is forced upon his death to travel to hell and ask for a place there. The Devil denies him entrance in revenge but grants him an ember from the fires of hell to light his way through the twilight world to which lost souls are forever condemned. Jack places it in a carved turnip to serve as a lantern.[5] Another version of the tale is "Willy the Whisp," related in Irish Folktales by Henry Glassie. Séadna by Peadar Ua Laoghaire is yet another version—and also the first modern novel in the Irish language.

Folklore

Asia

Aleya (or marsh ghost-light) is the name given to an unexplained strange light phenomena occurring over the marshes as observed by Bengalis, especially the fishermen of West Bengal and Bangladesh. This marsh light is attributed to some kind of unexplained marsh gas apparitions that confuse fishermen, make them lose their bearings, and may even lead to drowning if one decided to follow them moving over the marshes. Local communities in the region believe that these strange hovering marsh-lights are in fact Ghost-lights representing the ghosts of fisherman who died fishing. Sometimes they confuse the fishermen, and sometimes they help them avoid future dangers.[6][7]

Chir batti (ghost-light), also spelled chhir batti or cheer batti, is a yet unexplained strange dancing light phenomenon occurring on dark nights reported from the Banni grasslands, its seasonal marshy wetlands[8] and the adjoining desert of the marshy salt flats of the Rann of Kutch[9] near Indo-Pakistani border in Kutch district, Gujarat State, India. Local villagers have been seeing these sometimes hovering, sometimes flying balls of lights since time immemorial and call it Chir Batti in their Kutchhi–Sindhi language, with Chir meaning ghost and Batti meaning light.[8]

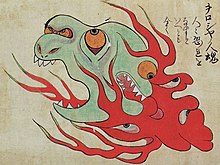

Similar phenomena are described in Japanese folklore, including Hitodama (literally "Human Soul" as a ball of energy), Hi no Tama (Ball of Flame), Aburagae, Koemonbi, Ushionibi, etc. All these phenomena are described as balls of flame or light, at times associated with graveyards, but occurring across Japan as a whole in a wide variety of situations and locations. Kitsune, mythical yokai demons, are also associated with will 'o the wisp, with the marriage of two kitsune producing kitsune-bi (狐火), literally meaning 'fox-fire'.[10] These phenomena are described in Shigeru Mizuki's 1985 book Graphic World of Japanese Phantoms (妖怪伝 in Japanese).[11]

Australia

The Australian equivalent, known as the Min Min light is reportedly seen in parts of the outback after dark.[12][13] The majority of sightings are reported to have occurred in the Channel Country region.[12]

Stories about the lights can be found in aboriginal myth pre-dating western settlement of the region and have since become part of wider Australian folklore.[12] Indigenous Australians hold that the number of sightings has increased alongside the increasing ingression of Europeans into the region.[12] According to folklore, the lights sometimes followed or approached people and have disappeared when fired upon, only to reappear later on.